At 2.23 pm on 4 June 1940 the Admiralty, in agreement with the French, announced that Operation ‘Dynamo’ was now completed. Over 330,000 British and Allied troops had been evacuated from the beaches and harbours of Dunkirk, in what Prime Minister Winston Churchill called the ‘deliverance of Dunkirk’. A similar fate befell Allied troops in Norway, who unable to prevent German forces advancing northwards, and with the situation deteriorating in France, were told to launch Operation ‘Alphabet’ – the evacuation from Norway. By the 8 June the evacuation was complete and among the British troops returning were men from the Independent Companies.

Drawn from the Territorials, ten Independent Companies of nearly 300 men in each, had been hastily put together in April 1940 in response to the German invasion of Norway. Formed as independent guerrilla units their task was to disrupt German attempts to utilise the Norwegian coastline between Namsos and Narvick.

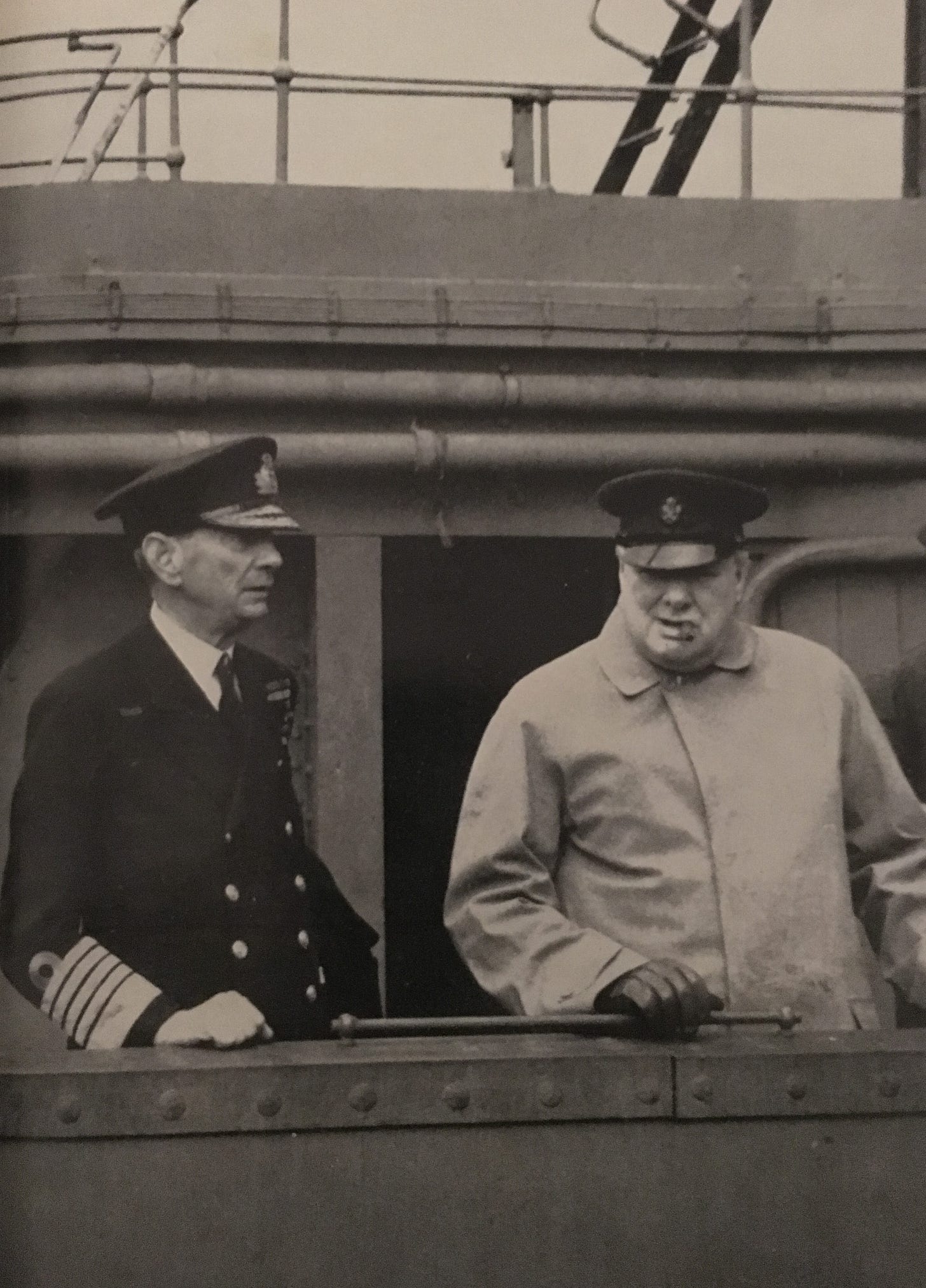

In the dark days following the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk, Prime Minister Winston Churchill demanded that under no circumstances would Britain resort to ‘the completely defensive habit of mind that has ruined the French’, and that work was to begin immediately to organise raiding forces that would strike along the coasts of the occupied countries.

In a note to General Ismay on 6 June 1940, Churchill said:

‘Enterprises must be prepared with specially trained troops of the hunter class, who can develop a reign of terror first of all on the “butcher and bolt” policy…I look to the Joint Chiefs of Staff to propose me measures for a vigorous, enterprising and ceaseless offensive against the whole German-occupied coastline…do a deep a raid inland, cutting vital communications, and then back, leaving a trail of German corpses behind them.’

Churchill’s urgency to resolve the matter was not lost on the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Sir John Dill. Within days, Dill had delegated the task to his Military Assistant, Lieutenant Colonel Dudley Clarke, to initiate the ‘butcher and bolt’ policy. Clarke, who had grown up in South Africa, had a profound interest in military history and enthusiastically recalled how after the triumphs of Roberts and Kitchener had scattered the Boer Army, guerrilla tactics by the Boer Kommandos had prevented victory for many months to come from an enemy vastly superior in numbers and arms.

However, it was by witnessing for himself groups of armed Arabs in Palestine doing much the same thing to a whole Army Corps from Aldershot, aided by thousands of auxiliaries, that convinced him that this type of irregular guerrilla warfare was what was required to take the fight back to the Germans.

Clarke stated:

‘Guerrilla warfare was always in fact the answer of the ill-equipped patriot in the face of a vaster though ponderous military machine; and that seemed to me to be precisely the position in which the British Army found itself in June 1940. And, since the Commando seemed the best exponent of guerrilla warfare which history could produce, it was presumably the best model we could adopt.’

Clarke outlined the concept of a new breed of British soldier which, he referred to as ‘The Commandos’, a name borrowed from a book about the Boer Kommandos by the South African author Denys Reitz. Clarke took his one-page outline to Dill, who presented it to the Prime Minister. Churchill, who had championed the idea of ‘storm troopers’, having seen for himself how effective they were for the Germans in the First World War, approved, and the Commandos were born.

Following Churchill’s approval of the Commando concept, Major General R.H. Dewing, Director of Military Operation and Plans, prepared a memorandum explaining the purpose of the new force and the way that it was to be organised and used.

General Dewing:

‘The object of forming a Commando is to collect together a number of individuals trained to fight independently as an irregular and not as a formed military unit. For this reason, a Commando will have no equipment and need not necessarily have a fixed establishment.’

Dewing detailed that irregular operations would be initiated by the War Office, with an officer appointed to command it, and that troops assigned to carry it out would be armed and equipped from centrally held sources. The process for raising and maintaining Commandos was also outlined in the memorandum:

‘One or two officers in each Command will be selected as Commando Leaders. They will each be instructed to select from their own Commands, a number of Troop Leaders to serve under them. The Troop Leaders will in turn select the officers and men to form their own Troop.’

At the time of writing his proposal Dewing had not decided upon the strength of a Commando, but did have ten Troops of roughly fifty men, in mind, with each Troop having a Leader and one or possibly two other officers. Indeed, ten Troops of fifty men was the structure initially adopted. Each Troop was led by a Captain and subdivided into two Sections with each Section further divided into two sub-Sections. Sub-Sections were further broken down into designated parties each with a specific role, which generally consisted of rifle, Bren gun and bomber parties. Sections were generally led by subalterns or senior Non-Commissioned Officers (NCOs), and sub-Sections by both senior and junior NCOs

Once the Commando Leaders had selected their men, they were to be allocated an area, usually a seaside town where they would live and train while not on operations. Dewing continued:

‘Officers and men will receive no Government quarters or rations but will be given a consolidated money allowance to cover their cost of living. They will live in lodgings etc. of their own selection in the area allotted to them and parade for training as ordered by their Leaders. They will usually be allowed to make use of a barracks, camp or other suitable place as a training ground. They will also have an opportunity of practicing with boats on beaches nearby.’

When a Commando was detailed for a specific operation, arms and equipment was to be issued on the scale required. Commandos were then moved to the location of the raid or operation, with a rule that operations should not last longer than a few days, and on completion they would return to their ‘home town’ to wait and train for the next one.

General Dewing pointed out in his memorandum that these arrangements should require practically no administrative requirements with regards to stores and equipment, however he did propose to appoint an Administrative Officer to relieve the Commando Leader of the burden of paperwork and that this officer would be permanently based in the Commando’s home town. The Commando organisation was intended to provide no more than a pool of specialised soldiers from which irregular units of any size and type can be very quickly created to undertake any particular task.

General Dewing detailed that:

‘The main characteristics of a Commando in action are: capable only of operating independently for twenty-four hours; capable of very wide dispersion and individual action; not capable of resisting an attack or overcoming a defence of formed bodies of troops, i.e. specialising in tip and run tactics dependent for success upon speed ingenuity and dispersion.’

In July 1940, Churchill appointed Sir Roger Keyes as Director of Combined Operations. Despite opposition from regular army authorities, the Chiefs of Staff instructed the five regional commands: Southern, Eastern, Western, London District and Household Division, and Scottish Command, to provide enough men for two Commandos per Command, with each Commando coming under the province of Combined Operations.

Twelve Commando units were originally raised. No.1 Commando was formed from the Independent Companies that were to be disbanded, but its formation was delayed due to the requirement for some of them to remain operational due to the threat of an imminent invasion by Germany. The original No.2 Commando was formed as a Parachute Commando raised from volunteers from all over Britain, and would eventually be re-designated as the 11th Special Air Service Battalion before becoming the 1st Parachute Battalion of the Parachute Regiment in September 1941. A second No.2 Commando was later formed from new volunteers under Lieutenant Colonel Charles Newman in Paignton in Devon. No.3 and No.4 Commando were raised from the Southern Command, with No.5 and No.6 from the Western, No.7 and No.8 from the Eastern, and No.9 and No.11 (Scottish) Commando from the Scottish. No.10 Commando was raised in the Northern Command but failed to be formed due to lack of volunteers and was eventually raised as No.10 (Inter Allied) Commando in 1942. No.12 Commando was formed later than the others and was raised in Northern Ireland, but due to limited resources only had an initial strength of 250 men.

From a pool of volunteers, Commanding Officers (COs) were selected to lead the new Commando units. CO’s were then responsible for selecting Troop Leaders; it was these junior officers who would then select from the hundreds of volunteers, NCOs and Other Ranks (OR’s), deemed suitable for Commando operations.

This selective system of reaching operational strength worked extremely well for the Commandos. With no shortage of volunteers, men of all ranks, and from all cap badges, were keen to escape the dull routine of wartime service. The selection process also enabled CO’s and Troop Leaders to stamp their own identity on the shape and development of the unit. It would be their ability to inspire and drive their new charges that would determine the operational success of the Commando.

Commanding Officer’s soon understood the importance of team spirit and camaraderie, and quickly grasped Churchill’s concept and vision for “specially trained troops of the hunter class”. Troops were formed around officers who had hand-picked men from their own regiments, men they knew and men they could trust, bonds were made that would remain unbroken through war and peace and that would stand the test of time.

Ian, what are your thoughts on the General Staff/Officer Class attitude toward the commandos (that they will never admit to publicly)? To this day, many French officers despise the autonomy of such units. Again, they will never admit to it openly but their disdain is palpable.